This is part two of the late Andy Baran's series of retrospectives on EGM and the gaming industry. This is the juicier of the two parts that we're able to put out, with behind-the-scenes tidbits that may surprise quite a few people.

This is part two of the late Andy Baran's series of retrospectives on EGM and the gaming industry. This is the juicier of the two parts that we're able to put out, with behind-the-scenes tidbits that may surprise quite a few people.

I wish I would've asked Andy if we could've published these sooner, while he was still around to see the feedback from the readers. But I guess I was hoping he'd get better and finish the stories himself. I'm sure he's still checking everything out from somewhere, though...ever the vigilant journalist, that guy. Andy, wherever you are, you'll be missed.

Evolution of an Industry, part 2

By Andrew Baran

Reviews were done at the end of the month, and since everyone shared the same document, often times the reviews would take on a similar tone. Ed Semrad did not write his own reviews while I was there (I wrote them, and before me, it was Danyon Carpenter). As a sign of rebellion, I'd sneak in clues to the reviews that would hint that Ed didn't write them. Speaking of subtle, subliminal messages were common -- and potentially legally disastrous. A keen eye can find some mighty interesting stuff hidden.

Photoshop was brand spanking new. When I started, only a handful of editors had begun piecing maps together using image frame grabs. Some of the staff still used the tried-and-true method of photos, X-Acto knives and a shitload of patience and tape. For years, the competition would be slow to the draw in regards to Photoshop. Nobody else in the industry would catch on for years, allowing our staff to create some of the greatest April Fool's Day jokes, such as the infamous Sheng Long trick (by Ken Williams, the SF2-loving Sushi-X).

The big tradeshow was the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), which hit twice a year: once in summer and again in winter. For us, CES was a chance to collect artwork for our pages. Before the consolidation of the industry, most domestic game publishers were small affairs, working out of plain, average offices that only housed a handful of people. They didn't have armies of teams working day and night to churn out franchises, and there weren't any artists on-hand to provide artwork (a reason why early game art sucked so badly). Few had public relations reps, and those that did had no interest in games.

At the time, Japan was the big hub of game design. All the best titles came from there, with a few notable exceptions coming from the UK studios. Console games made in America were considered crappy, and that's putting it nicely. PC was where the best US developers dedicated themselves. The support that the Japanese companies gave their domestic branches was minimal at best, and the time it took to release a game here in the States after its Japan launch was often a year or more.

The biggest game genre was the shooter. Not the modern FPS, but your typical twitch-gaming-reflex outer-space shooter. Action platformers were on the rise, thanks to Mario and Sonic attracting and building the gaming audience. RPGs were a niche market and few companies gave them a chance here in the States. Games that featured anime in any form were considered "too Japanese" to be released here, with few notable exceptions. These were often dramatically westernized if they did see our store shelves.

While we're on the topic of stores, it's worth noting that game stores were far different. They did not take reserves, and they didn't accept trades or sell used product. Funcoland, the first franchise to do so, would not surface for awhile.

Although the Turbo was falling by the wayside, the NES and Genesis continued to battle for dominance. At this time, Super NES had yet to be released.

Back to CES...

Since CES was the best chance to showcase product, it was one of the few times when a publisher would care (or be able to pressure the Japanese branch) to provide artwork. In regards to documentation, information from companies simply did not exist. Getting interviews from anyone, even a PR rep, was nigh impossible. This is why a lot of early EGM copy seems like a shot in the dark -- it was.

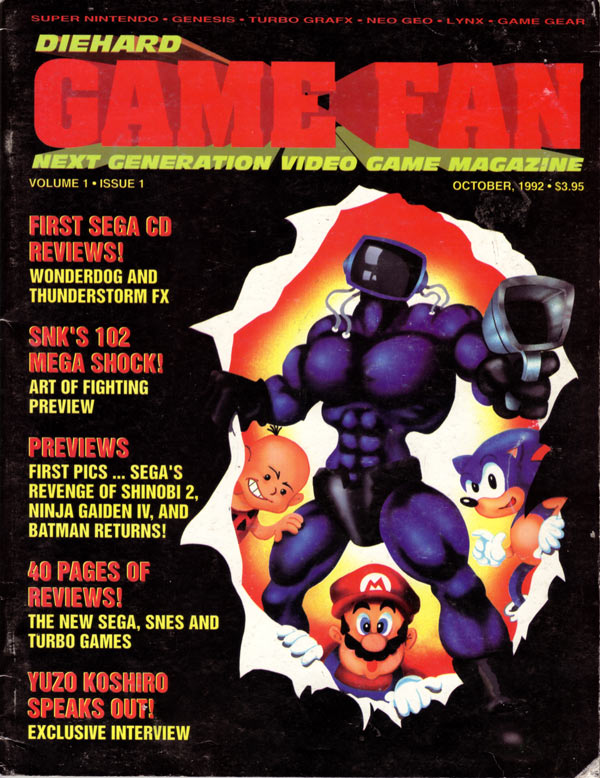

CES was also a chance for the staff to get seen. Many editors were forbidden from using their names outside of the masthead. Steve Harris was afraid that we'd be poached away by the competition, with paranoia about Diehard GameFan being the biggest boogeyman out there. Just talking to someone from the competition could get you in big trouble.

Company relations were usually maintained by Jon Stockhausen (third-party liaison) and Ed Semrad. We were not allowed contact, unless our offices were visited. Jon was really the hub through which nearly all of the gaming content flowed. His contributions to EGM have never been recognized by the readership, but he truly was the unsung hero.

Both Ed and Jon received game promos every now and then, but it was a rarity. Maybe a cool piece of swag would come in once or twice a year. Free games from companies were not allowed and they usually ended up as giveaways for our various contests (or given to Ed's son).

There was no Internet back then. Sit back and let that soak for a sec.... Can you even imagine that time now? Forget about emails. That line of communication just didn't exist. Faxing was the height of our communication -- that and the fact that we shared about six phones for the entire company.

For all of our troubles, we were compensated well. Raises ranged between 8-20% each year and for a bunch of kids still either in or just out of high school, it was a fortune. The staff of EGM was young and able to put in all-nighters and subsist on a steady diet of Taco Bell and Mountain Dew. Our health was a secondary consideration, placed below gaming. We were a close-knit team...a family.

For all of our troubles, we were compensated well. Raises ranged between 8-20% each year and for a bunch of kids still either in or just out of high school, it was a fortune. The staff of EGM was young and able to put in all-nighters and subsist on a steady diet of Taco Bell and Mountain Dew. Our health was a secondary consideration, placed below gaming. We were a close-knit team...a family.

We were all hardcore players, every last one of us. Several of us had gaming world records under our belts, and these talents were our ticket into the industry.

That's how it was back then...

Next up: the middle years of EGM and how things began to congeal into something a little more recognizable. It's an EGM era I like to call the Age of Expansion.

Unfortunately, that's as far as Andy's gotten with these articles, so we won't get to see the "next up."

Comments (15)

The staff of EGM was young and able to put in all-nighters and subsist on a steady diet of Taco Bell and Mountain Dew

Andy was a unique person that will be missed by all!

LeFebvre (Candyman to us old timers) hit it the nail on the head.

Andy was as unique as they come and personified individualism.

Even on the magazine in the early days his passion would come out in the thoroughness of his Fact Files. I may have had to help a little with art direction, but Andy would play a game backwards and forwards regardless of it quality.