Good humor, as most of us have come to realize, is a rare commodity in games, and with good reason. It’s an incredibly difficult and unscientific challenge to integrate resonant and effective comedy into the formal language of games. There’s no algorithm for it and developers can usually be forgiven for bombing. Like many young comics, you need to imitate Pryor and Hedberg and Carlin before you find your own voice. You bomb, and bomb, and bomb some more, until finally you’re armored and develop your own style and refine your material. The problem with game approaches to comedy is that it’s a tricky venue to explore, and you may work on refining that material throughout a 2 or 3-year development cycle before it gets much of an audience, just to find out it resoundingly bombed at launch.

Good humor, as most of us have come to realize, is a rare commodity in games, and with good reason. It’s an incredibly difficult and unscientific challenge to integrate resonant and effective comedy into the formal language of games. There’s no algorithm for it and developers can usually be forgiven for bombing. Like many young comics, you need to imitate Pryor and Hedberg and Carlin before you find your own voice. You bomb, and bomb, and bomb some more, until finally you’re armored and develop your own style and refine your material. The problem with game approaches to comedy is that it’s a tricky venue to explore, and you may work on refining that material throughout a 2 or 3-year development cycle before it gets much of an audience, just to find out it resoundingly bombed at launch.

There are so many discrete challenges in the game-comedy problem, it’s hard to know where to start. How do you create a comedic in-game character with a broad and subtle reach? How do you make the mechanical logic and sporting performance of gameplay funny and varied? How do you introduce a comedic layer that doesn’t feel awkwardly estranged from the gameplay? Etc. etc.

Recently, however, first with Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP in late March, and now Portal 2 in April, these two games have endeavored to deliver some running in-game comedy, yet not in equal measures, not in equal style, and certainly, not in equal strength and success. But one trait they share is a penchant for meta-humor; jokes that implicitly or explicitly satirize and exaggerate aspects of the medium and player behavior. They both rely heavily on linear dialogue payloads as the dominant delivery method, but both games package their satirical commentary differently and have very different things to say. And, in my opinion, one is funny and the other is as lifelessly one-note and expressionless as a dead baby joke.

Be advised, there are something in the way of spoilers ahead, but they are minor and mostly vague. I’ll set the spoiler threat level to “GUARDED” (Blue).

Portal 2

The original Portal presented some of the richest skewering of games from within a game, through dialogue, interactive situations, and objects. Perhaps that’s why for many players like myself, the memeification and overuse of many of Portal’s cleverer, compact, and catchy punchlines led to exhaustion, and irritation at the mere mention of them. Nevertheless, the game is not at fault for how it inspired a movement of its fans to beat all the funny out of some of its jokes. The movement occurred because smart, subtle, suggestive, but most importantly, funny in-game criticism of gaming tropes is virtually non-existent.

So, it sort of makes sense that many fans were ravenously propagating these punchlines because it was virtually the only well to draw from for memorable in-game witticisms that challenged the conventional and redundant wisdom of what a game could or should do. You didn’t even need to really think analytically about what the joke meant in a larger conversation on play, it was sort of intuitive and understood, even if you couldn’t fully articulate why it was funny.

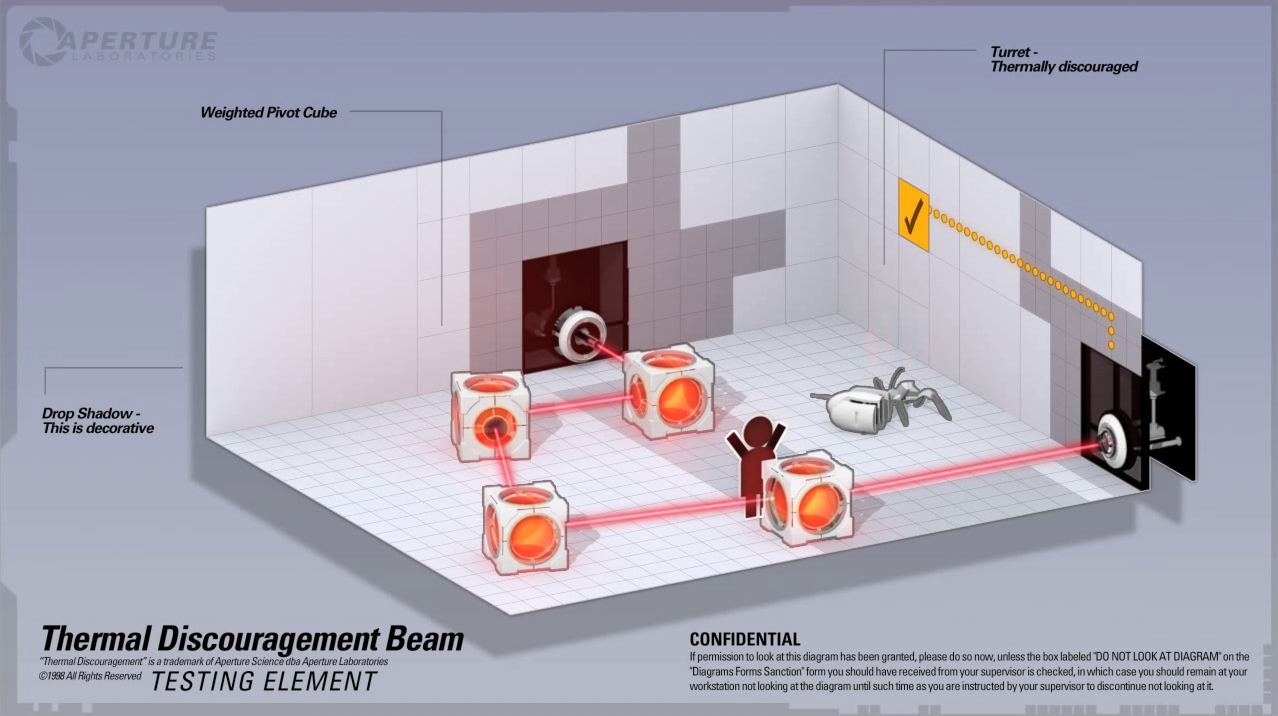

The Companion Cube is a symbol for lifeless objects the player is routinely told in other games are characters they should empathize with and care for. The cube’s bare polygon primitive form resembles placeholder art or a character node in a level editor, a reductionist statement that strips away the façade of an empty character and shows it for what it really is, an expressionless object.

The baleful, macabre, and matter-of-fact testimony GLaDOS gives about the perils of test subjects past is an amusing allegory for game testing, designer scare tactics, prohibitions on unwanted player behavior, and other dimensions of behavioral psychology in game design.

The cake -- yes, that sickeningly sweet treat many fans pigged out on -- represents an inedible and intangible material reward of superficial value, used to extrinsically motivate the player into desired action that furthers game progression. Call it a carrot on a stick, call it a wedge of cheese in a lab rat’s maze, or a toy for good behavior, the cake turns out to be an empty MacGuffin, the blank and inanimate spoils of a grind, an insubstantial incentive to goad you through the labyrinth -- mindless design comfort food.

This time around in Portal 2, there’s no confectionary MacGuffin, the comedy is much more situational, and it’s the creative process of game design that serves as one of the more central subjects for its humor. Once GLaDOS resumes her custodial labor of maintaining the presentation and functionality of Aperture’s test chambers, she begins to talk about the “testing” process. It’s like an addiction for her, to design test chambers, to feel that “solution euphoria” that comes from a test subject completing a chamber. Essentially, as the omnipotent, all-seeing, master tinkering mind of Aperture, she exercises her hungry god complex. She tests not to further any scientific hypothesis; she enjoys the act of creation, and observing how you -- the tiny, powerless gnat -- will suffer and survive her perilous art. At times, she says, the slog of designing and maintaining such a grand amusement park can be torturous and wearisome, but you pull through and keep on testing. You can hear the rigors and rewards of game development in these asides.

Halfway through the game, you enter the bowels of Aperture Science and explore the tarnished and derelict R&D experiments of its past. The voice of Aperture’s CEO and founder, Cave Johnson, booms through a PA system, colorfully explaining the many messy, broken, and insane hypotheses they entertained, usually at the cost of test subjects’ physical and mental health. You walk through areas labeled “Alpha” and “Beta”, stages for projects at particular phases of development, not unlike the development phases of games, which adopt the same naming scheme. These areas are tinged with a dark comedic insanity centered on catastrophic missteps, harebrained inventions, and exceedingly poor decisions that guided scientific development. Essentially, this is the exaggerated comedy of game development’s iterative process.

Then, you encounter signage and some of Cave’s recordings that promise $60 to participating test subjects. This dollar amount is not arbitrary. In one room, you can se a framed picture that depicts a beaming test subject clutching wads of cash. Another shows a jubilant test subject jumping for joy in a snazzy suit, with a large yacht in the background that has a $60 price tag attached to it. The joke is that gamers often expect unreasonable and superfluous value from their $60 purchases. This comment was ironically prescient considering some of the inane outrage that gamers directed at Portal 2 once it shipped, who bellyached and moaned about how the game was too short (some even making preposterous claims that it only took them 2 hours to complete single-player) and not worth full retail value. Cave also comments on his testers, “What is it these people buy? Tattered hats? Beard dirt?” No doubt a veiled insult to the hipster demographic of the buying audience, and what they choose to spend their money on.

LEVEL RED SPOILER APPROACHING. SKIP TO THE KEYWORD "TOPIARY" IF YOU WISH TO AVOID IT:

Bad and misguided game design is also an important aspect of the farce. When GLaDOS is deposed and succeeded by a new cybernetic overlord of Aperture, the design of test chambers changes. The new proud creator arrogantly challenges you to complete their first original test. It’s one of the simplest and most boring puzzles in the game, and it comes more than halfway through. Not knowing what to do and caught off guard by how quickly you completed it, the new creator forces you to solve it again, masking his inexperience by proclaiming that it’s perfect and should just be repeated endlessly.

GLaDOS, the design veteran, ridicules him and his shoddy design enough that he begins adding new chambers. Then, he pulls from a stockpile of completed chambers that GLaDOS once designed and starts mashing them together in some inelegant way to make them his own. After a number of these copy and paste, dissection and reassembly chambers, he proudly announces that you are entering a chamber that he designed entirely on his own. GLaDOS immediately recognizes it as a counterfeit of one of her own tests, to which your new bumbling overseer defends himself by pointing out that he added the word “test” to one of the walls, in his mind validating and exonerating his blatant plagiarism.

This cosmetic alteration of space, as an attempt to conceal the fingerprints of thievery, is an indictment of similar cases of petty theft you can find everywhere from the mod community to top-tier development, from derivatives to clones. The humor lies in the transparency of the cover-up and the foolish belief of the counterfeit artist that the player and creator will be none the wiser, like copying Crazy Train, but changing one chord.

"TOPIARY"

Throughout the above sections, the joke is intentionally bad game design, further heightened by the fact that the choices and sensibilities manifesting in physical space are so far removed from what you would expect from premium Valve polish. Portal 2 introduces this new comedic theme of authorship and mad creative invention in games, but it also builds on its predecessor’s primary comedic preoccupation; the limitations of games, and timeworn narrative and gameplay trappings.

At the beginning of the game you are awoken from cryosleep by a tinny robotic voice, inside what looks like a cheap motel room. The voice issues a command to look at the ceiling and then the floor, for a “Mandatory physical and mental awareness exercise.” This is the routine physical examination of most first-person games, going through the motions of getting the player acclimated and oriented to the most basic control functions. Then, you are ordered to go to sleep. You awake to the same room, but now dark and frightfully deteriorated. You have been in cryosleep for quite some time.

Before long, a spherical service robot named Wheatley enters your room. He informs you that due to your irregularly long hibernation, “It’s not out of the question that you might have a very minor case of serious brain damage.” He asks, “Do you understand what I’m saying? At all? Does any of this make any sense? Just tell me, ‘Yes.’” A prompt appears on-screen indicating that you should press the action button to “speak.” By pressing the button, you jump up in the air. Wheatley responds to this non-verbal response by adding, “What you’re doing there is jumping. You just… you just jumped. But nevermind. Say ‘Apple’. ‘Aaaapple.’” The same button prompt appears. You press it, you hop up slightly like a dog begging for a treat, and Wheatley resigns by saying, “That’s close enough.”

The customary eye exam and toddling tutorial is a rather patronizing order to follow for those of us who have ever played a first-person game before. It does almost imply that you must have brain damage if you don’t know how to look up and down and put one foot in front of the other virtually.

Your inability to speak is a figurative rendering of almost every single player character in videogame history. You don’t ever truly have a voice in a game. Every player character -- that is supposed to be a portrayal of a living, breathing human -- does have some form of brain damage, like massive trauma in the left temporal lobe that prevents the formulation of language. You are a mouthless armature of muscles, joints, and nerves. The action button is your voice. You commune with the world through kinetic means -- bombastic and broad sweeping gestures of injury and action -- and not by introducing logic and autonomy into a narrative system. As the mute, brain-damaged cipher hero, other characters don’t want or need your opinion, you just pull the plow of progression along and let the adults talk in whatever forum they choose.

Portal 2’s co-op mode explores many other comedic themes that its single-player mode doesn’t, or only touches on in a cursory way. Both players control two robots that must solve new sets of spatial puzzles with GLaDOS chirping snotty comments at them all the while. In the second series of chambers, GLaDOS remarks, “This course was originally designed to build confidence in humans. To do that, the tests were nothing more than five minutes of them walking, followed by me praising them for another ten minutes… on how well they walked. Since you are thankfully not humans, I have changed the tests to make them far more challenging and far less pointlessly fawning.”

In the last room of the chamber, the area is cleared when a ball is dispensed and one player places it into a cup, which opens a door that leads to the end zone. GLaDOS’s monotone voice pipes in, “You did an excellent job placing the edgeless safety cube in the receptacle. You should be very— Oh wait. That’s right, you’re not humans, I can drop the fake praise. You have no idea how tiring it is to praise someone for placing an edgeless safety cube into a receptacle designed to exactly fit an edgeless safety cube.”

These remarks criticize a growing trend of positive reinforcement in games. With Peggle, you sit there and stare at a ball making its way downscreen, batted this way and that by the forceful persuasion of luck and chance while feedback explosions scream out some higher purpose to your haphazard shot. In many contemporary RPGs and action games, NPCs kneel at your feet and laud you for being such a good person and the savior of mankind, which most likely required very little work or challenge to win their little hearts and minds. But the coddling of players is most evident in many casual and mobile games now, which often spit out cacophonies of color, exclamation points, and kind adjectives and achievement points for fitting the shaped block through the right hole. GLaDOS’s opinion of this matter might not be the most comically successful of her snark-filled quips, but it is rich in suggestion.

Of all the above comedic constituents, and the many more I have not mentioned, it is only the patronizing coddling of players that Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP also explores.