I wholeheartedly agree with Patrick that cut-scenes need some revision -- someone needs to send an editor to the Kojima offices, for instance. I don't particularly like superfluous sequences that break the gameplay's flow; however, I don't think quick-time events are the answer, either (as I've written before). I still think the closest we have to seamless narrative in video games is the Half-Life approach that puts a premium on interactive storytelling (to a degree).

Characters suddenly become unplayable as the player becomes aware of new pieces of information. Armed with that knowledge, she embarks on the next quest or level and gets right back into the action.

At first glance, this completely makes sense. After all, if games want to tell a story they need to have some type of narrative anchor, and cut-scenes are a great way to do that.

Since the mid 1990s, games have used pieces of cinematic animation to bridge levels and create motivation to drive the story forward, which demonstrates that the industry clearly wants to tell stories. Ever since the plot moved on from “the princess is in another castle,” games have wanted to create new forms of narrative that drive the player forward.

Cut-scenes can provide a default way of showing the personality of a character, which can be a particularly fickle trait in something as subjective as gaming. They provide a canon, stability, and a solid story arc in a game filled with thousands of options for each player.

But is it time for the industry to outgrow cut-scenes?

They may very well provide a method for giving solid narrative, but the use of in-game narrative has grown over the past decade, a trend which primarily started with Valve’s Half-Life in 1998. This was one of the first titles to never break away from the viewpoint of the main character, which made all of the story elements filter through the player’s gaze.

The advantages of this are obvious with the main benefit being that you can direct the gamer down a certain path and make them take note of certain elements within the story, or simply tell them while having them retain control.

Because after all, the importance of the game is control. Developers want gamers to be in control at all times, and that is much, much superior to having them watch a cutscene.

But a number of different disadvantages reveal themselves when you simply relying on cutscenes, especially when new titles are becoming so good at using in-game and in-character narrative.

Firstly, cut-scenes are used far too often. As previously stated, the purpose of the game is to interact, play, and feel control. Cutscenes detract from that feeling, and they need to be used sparingly as a result.

Secondly, cut-scenes are often used for little or no purpose. The most recent Medal of Honor sported several cut-scenes that provided no other information than watching the character stab or shoot someone. What is the point of this? Why can’t the gamer have done it herself?

Finally, cut-scenes can distract the gamer from her actual goal. When she sits down to play a game, she doesn’t necessarily want watch a film. She has a DVD or Blu-ray player for that. Rather, she wants to actually engage and control a character.

She want to dictate exactly how she handles herself, uses weapons, talks, jumps, or runs. And she wants to feel that power at all times. Cut-scenes break that power and turn the gamer into a passive agent once again; in some ways, it directly contradicts the purpose of the medium.

Debate surrounds Activision Blizzard hinting that the publisher may at one point take all the cut-scenes from Starcraft 2, stitch them together, and sell them as a movie. They estimate they could make millions of dollars doing this. They are probably correct. Gamers would pay through the nose to see this type of “film" -- if this product could even be called that at all.

But in theory, that plan shouldn’t even be allowed to work. Cut-scenes need to be a tool in the writer’s arsenal -- not the means by which they tell an entire story.

Just as a screenwriter does not rely entirely on either dialogue or on-screen action to completely tell a story, games must rely on both in-game action and well-crafted cut-scenes to provide the full breadth of characterisation and action the narrative deserves.

Both tools cannot make sense without the other present -- they must work in tandem. The perfect scenario would see Activision Blizzard’s film be nothing more than a group of shots that have no context when put together.

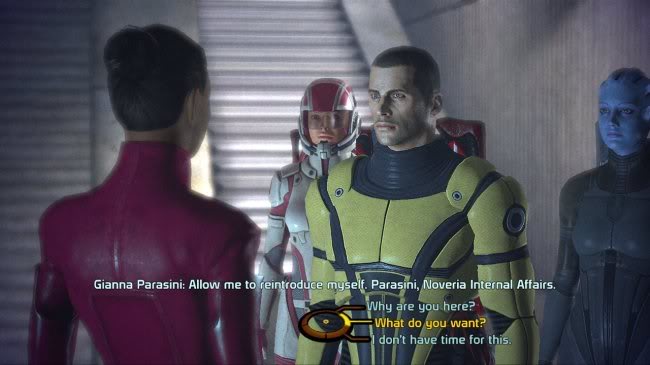

The best examples of games that properly use cut-scenes are Mass Effect and Knights of the Old Republic. For the most part, these games rely on cut-scenes when the user controls the action. She choose the dialogue the character speaks -- and to some extent, the response -- and then what happens next in the narrative.

In this situation, the gamer has at least some essence or perception of control about what is happening directly on the screen, even though she cannot control the actions of the character at that particular time.

And that is the purpose of the cut-scene -- to provide a cinematic experience that gives the gamer some excitement without completely losing that element of playability.