We're back from holiday with the computer role-playing game retrospective. This week, Reggie focuses on Interplay, the publisher who released one of favorites: Fallout. Catch up with Reggie's look at Strategic Simulations, Inc., Origin Systems, and Sir-tech.

Interplay: From Bards to Bombshells

1983 - Present

Interplay once dominated computer role-playing games in the late eighties alongside its peers. Although they would later be known as a publishing powerhouse responsible for Black Isle's Fallout series and Planescape: Torment in the late nineties (along with the revolutionary Descent franchise), it started with an idea, a game, and a programmer who wanted to kill lots of monsters.

Interplay once dominated computer role-playing games in the late eighties alongside its peers. Although they would later be known as a publishing powerhouse responsible for Black Isle's Fallout series and Planescape: Torment in the late nineties (along with the revolutionary Descent franchise), it started with an idea, a game, and a programmer who wanted to kill lots of monsters.

Brian Fargo wasn't the stereotypical coder living in his parent's garage or a student at a place like Caltech. He was a sprinter on a track scholarship when he walked out of school to work on his first game: Demon's Forge. Like Richard Garriott and Jon Van Caneghem (New World Computing), his house was literally his office as he managed marketing and sales from his bedroom.

The company he put together around the game was sold in '82, which pocketed for the then-19-year-old Fargo a cool $5,000. Interplay wasn't around yet, but a company called the Boone Corporation had folded some time afterwards and left quite a few gifted programmers without jobs. Several of its laid-off employees -- including Rebecca Heineman -- then banded together with Fargo to help found Interplay with a little boost from a generous $60,000 windfall from a new client.

But not to make games.

Interplay's first contract was from World Book Encyclopedia to do a series of small titles. That didn't stop a young Activision Inc. from stepping in later and handing Interplay a contract for three adventure games to the tune of $100,000. Despite creating Mind Shadow under contract, Interplay was still an indie, and that left the door open for Electronic Arts to publish one of the genres most memorable CRPGs.

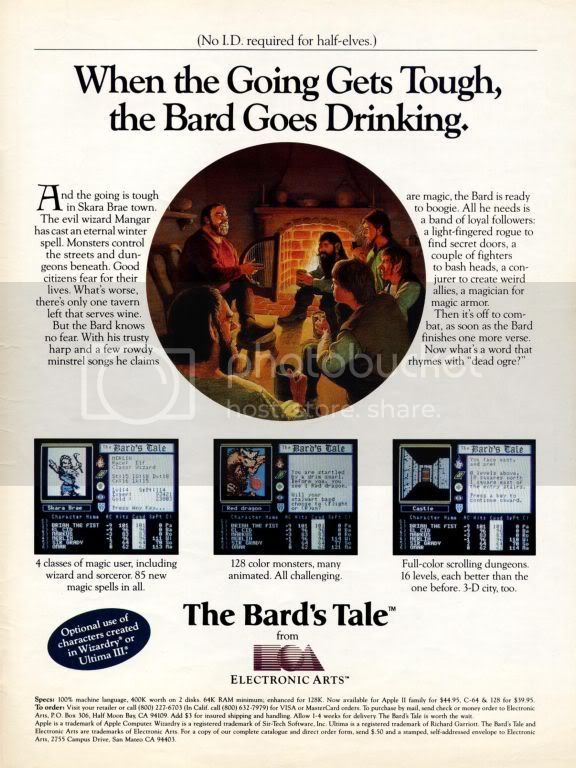

The Bard's Tale was the result: a simple-to-use party system, a wide variety of dungeons, animated monster portraits, and a magic interface that relied on knowing the four letter codes for each one as a form of copy-protection. It also helped that The Bard's Tale was far more forgiving when it came to death when compared to Wizardry's then-brutal incarnations.

Although the series wasn't known for having interactive NPCs and consisted of combat-heavy dungeon crawlers, each game relied more on a player's imagination to fill in the blanks when it came to story; however, The Bard's Tale series would begin weaving its own mythology in between its chapters. Vast dungeons filled with devious traps, darkness shrouded halls, spinning floors, and mobs of monsters proved enough reasons to religiously back-up character disks.

As fantastic as the games were, The Bard's Tale series also had its own ups and downs. As Rebecca Heineman recalls in an interview with Matt Barton on Gamasutra, the second game was intentionally aimed at killing players (via the Death Snare dungeon puzzles) than in being as fair as the first and third games. This was apparently thanks to the Lead Designer Michael Cranford's preference for being the kind of me-against-everyone Dungeon Master who likes seeing players die. But as Fargo's high-school friend, I guess he had earned a little leeway in what he wanted to do.

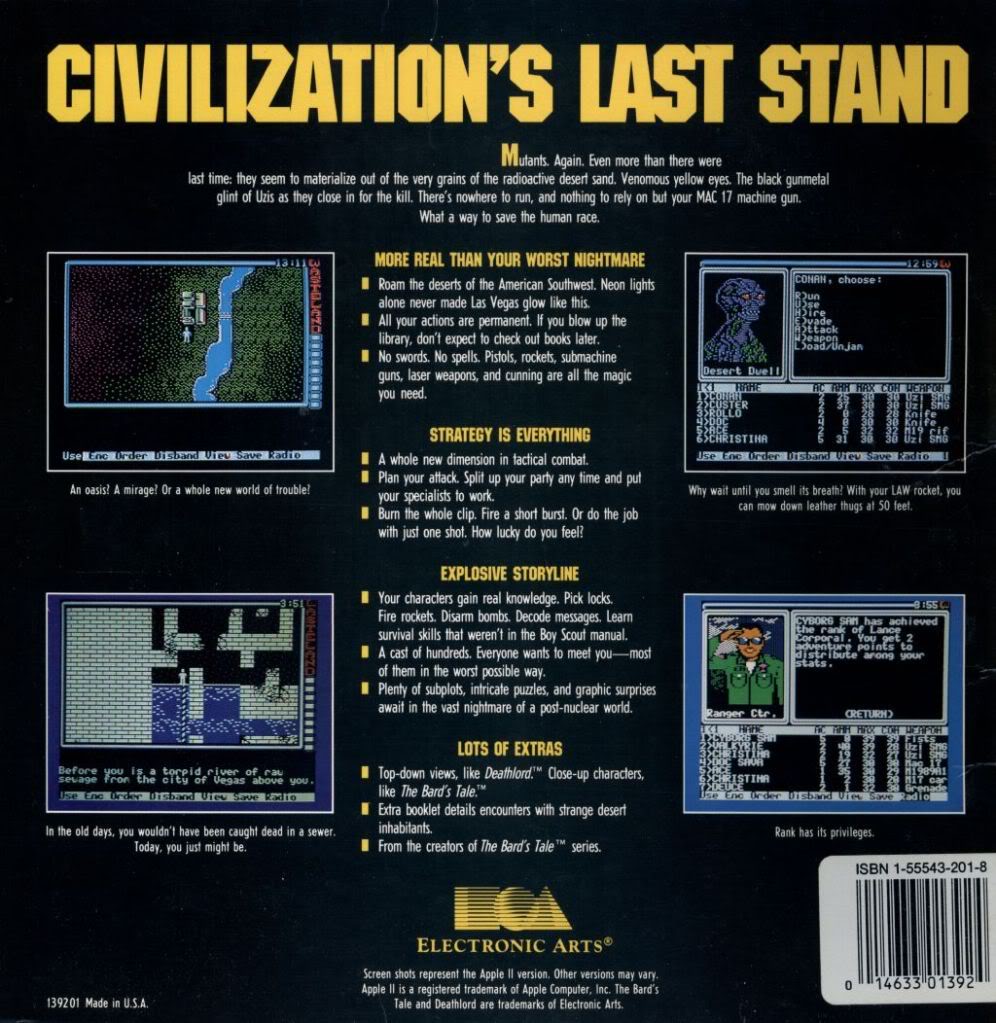

In '88, Interplay would go on to kick elves, dwarves, and orcs to the radioactive curb in Wasteland, a post-apocalyptic CRPG that shied away from swords and sorcery and replaced them with automatic weapons and a vast, player-customized skillset. Its minimalist looks and top-down tiled approach went against The Bard's Tale's first-person perspective, but the wide array of skills and open-ended depth of its gameplay more than made up for what it lacked on the surface, which provided ideas that would later be passed down to titles such as Fallout.

Dragon Wars, considered by some as the spiritual successor to The Bard's Tale, went back to high fantasy in '89 -- complete with fancy graphics and a hybrid of features that felt as if they were a culmination of Interplay’s work from Wasteland and The Bard's Tale. It also exemplified the kind of storytelling that Interplay had been known for. Remember, this came out when the Cold War was still on, so casting dragons as the equivalent of nuclear weapons in a world gripped by magical oppression were intentional real-world parallels.

And as cool as that might sound, that wasn't what Dragon Wars was supposed to be. Instead, it was supposed to be The Bard's Tale 4.

At the time, Interplay looked to break away from EA's publishing empire and would eventually become an affiliate with Mediagenic (which was actually Activision suffering from a bout of identity indecision). Unfortunately for them, EA owned The Bard's Tale trademarks -- not only the name, but the world and everything associated with it . Predictably, EA didn't take too kindly to Interplay’s move and literally took its Bard's Tale ball and went home, which forced Heineman and the rest of the developers to leverage in the changes at the last minute. At least now I know why the dragons didn't look like...well...dragons. But as last minute fixes go, kudos to Heineman and company for actually making it work as well as it did.

Interplay had also adapted William Gibson's Neuromancer as a hybrid adventure/RPG, which brought the cyberpunk classic to PCs. Varnished with every cyber'ed syllable from Gibson's universe, walking the world and then jacking into cyberspace to duel ICE and nigh-omnipotent A.I. watchdogs protecting their master's secrets was as close to the vision of the book as anything else would approach at the time. Software and cyberdecks replaced swords and armor, and character interactions were handled as an adventure game in 'the real world.” It was an amazing title with a soundtrack by Devo, and it ran pretty well on a computer with only 128K of memory.

Interplay was also renowned for several other unique titles under its belt such as Battle Chess and Borrowed Time as well as bringing in actual writers to help with game design such as Arnie Katz, Bill Kunkel, and Michael Stackpole.

But Interplay wouldn't survive as a RPG powerhouse.

Read on to page two for Interplay's fall from grace.