Everyone's talking about the 25th anniversary of Mario. This week brings with it another game's birthday, yet one slightly less revered: Kenji Eno's strange little puzzler You, Me, and the Cubes for WiiWare. Though far from perfect, the experience of playing this game is quite unlike any other I've had. And few people gave it a chance. So while everyone else fetes our man Mario, permit me to shine a light on these nameless, ethereal creatures called Fallos...

---

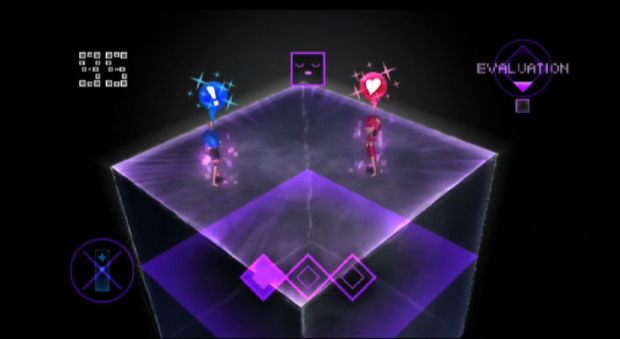

I wanted to love this game. The concept—toss sentient humanoids called “Fallos” onto floating cubes while maintaining the structure's balance—lured me in with its disregard for traditional puzzle elements. And yet that's exactly what it is: a puzzle game. With living, moving pieces.

When I first saw screens of the Japanese version, called Kimi to Boku to Rittai, I fell for the minimalistic oddness, the purplish-glow emanating from everything. But the game seemed far too bizarre for Western tastes; surely my only experience would be a few views of the serene trailer and a continued wish for more imports landing on North American shores.

But then, at E3 2009, a small booth showed off a game called You, Me, and the Cubes. This was it. The developer fyto (From Yellow to Orange), headed up by Kenji Eno (of the survival horror series D) was bringing it out to America, published by Nintendo. When it released in September 2009, I quickly burned 1000 points and downloaded the title. And though the existence of this game is a good thing for the future of niche Japanese titles coming stateside (see also: Muscle March and Tomena Sanner), the overall product fell short of my high expectations.

The game itself is fairly simple. A cube floats in space. You are given a set amount of time, and are tasked with a specific number of Fallos to land on the cube. In the one-player mode, you throw two at once; play with a friend, and each controls a separate Fallos, making cooperation necessary.* Aim them correctly and the cube remains level. Throw one too far to the left or right and the cube will tip, resulting in one or both of the creatures to fall down and ultimately slide down into the abyss. Once the alloted number of Fallos are on the cube, a countdown begins. If it reaches zero and they're still on the surface, you've won that stage; any Fallos on its feet then sits down, attached to the surface for good, while those sliding or scrambling around will slide off, emitting a shrill cry, accompanied by a word bubble saying “Why me??” or “Ayeeee!” Another cube then materializes, merging with the previous one, with a new time limit and task. With each new cube things get trickier, as you must land at least one Fallos on each surface. The final geometric shape is a conglomerate of six cubes in total; successfully balance the required amount of Fallos, and you win the level. The payoff? Each creature still stuck to the multi-sided shape is counted, turns into a dove, and flys away.

If you're anything like me, the first time you experience a stage in full you will sit wide-eyed and silent and think: This... is amazing. And it is. At first. The spacey, purgatorial atmosphere presented in this game is beautiful and spooky in a way that no other game I've played is. This comes from a few factors, among them a moody score and the translucent, lo-fi modernist graphics. What makes this game both disturbing and somewhat frustrating, however, is that your game pieces are actually alive. These are no lifeless L-shaped blocks you're manipulating; you're tossing moving creatures into a situation, and once you've released them, they move about on their own. Herein lies both the game's charm and perversity. When that cube tips and and the blue (male) Fallos falls down, it doesn't just disappear. The little man scrambles to get up. His arms flail. You can almost imagine tiny nails scratching into the cube's pristine surface, hoping for an inch of friction to save him from the black doom below. A pink (female) Fallos nearby might walk over and try to save her fellow creature. But if she doesn't arrive in time, it—he—falls, and screams in agony. You, the player, are witness to a death, or at worst, an accomplice. Depending on your mental state, this game is brilliant—some kind of psychological exercise in voyeurism—or utterly sadistic.

The way you control the game is equally compelling. Each move consists of three steps: first, you shake the Wii-mote to create the Fallos inside the remote; then, point at the screen and select your landing position with a press of the A button; finally, do a throwing motion and the Fallos will fall toward the cube, as if you'd just thrown them from outside the screen. Though some might find the constant shaking and gesturing egregious, I found it wonderfully immersive. This is a game which could only properly work on the Wii—substituting button presses for the motion controls would vastly limit your own connection to the action on-screen, cutting you off from the strange sight of seeing your own creations slide irrevocably to their doom. The speaker on the Wii-mote is also used to great effect: When you shake it enough, a mechanical sound effect emits from your speaker, telling you the Fallos are ready. Once in awhile, you'll hear a different sound, one more ominous—you've just created a Pale Fallos. This creature roams the cubes, pushing others down and wreaking havoc on your carefully maintained balance. To destroy it, throw two Fallos on the Pale one, and you're rewarded with ten extra seconds.

The game's limitations are found half an hour in, when you find yourself still throwing little people on floating cubes and waiting for something else to happen. New cube forms arise: Push Cubes, with shifting borders that shove Fallos off; Freeze Cubes, that solidify the entire structure for a few seconds once the guys land; Cap Cubes, with a lit-up number stating the maximum amount of Fallos allowed on a surface, among others. But the main mechanic is the same throughout: Throw dudes onto a cube, throw more dudes elsewhere to balance it, throw some more elsewhere, etc. Don't think its simplicity equals a lack of challenge: In the later stages things get rough. More complex cube arrangements, coupled with more required Fallos in much less time, all combine to create a very tricky game. Because of this, all initial stages are accessible from the beginning. (Another set are unlocked after you complete all levels.) With each level won, the game rewards you with a subtle surprise: On the level select screen, each completed level, represented by a grid of squares, sounds out one tone in a longer sequence. The more levels won, the more tones of the longer song you hear. It's eloquent details like these that lift this game above mere 'failed experiment,' and provide an aesthetic depth beyond the seemingly shallow gameplay.

If all of this sounds overally abstract, or just weird, this might not be the game for you. But for those who want to try a different kind of gameplay, with atmosphere and style, I wholeheartedly recommend You, Me, and the Cubes.

(a version of this review was originally posted on WarpZones.com)

--------